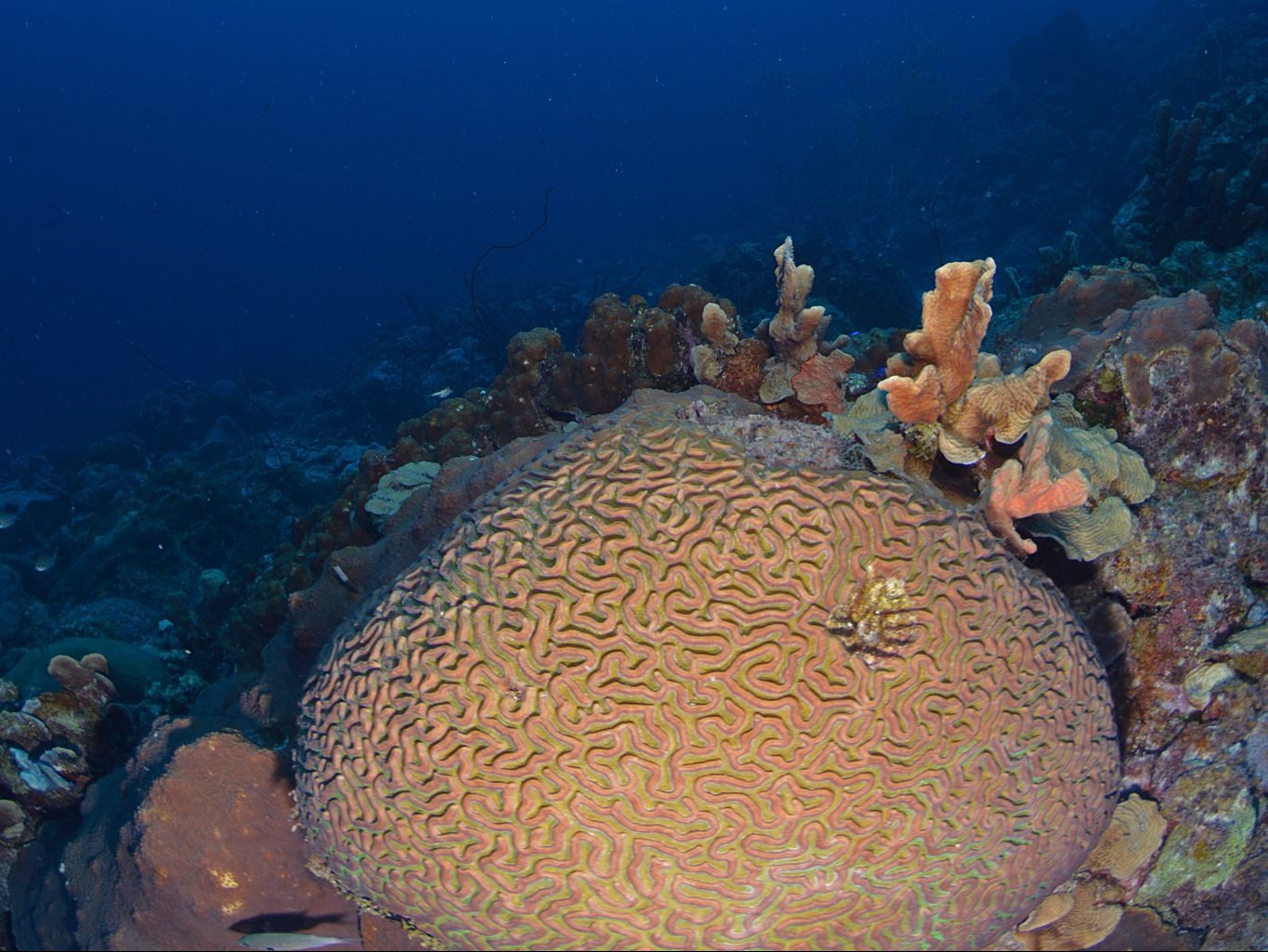

Curaçao coral reef pre-SCTLD outbreak

In the summer of 2018, I embarked on my first dive trip in the Caribbean, spending the majority of the summer taking a college course in Curaçao. It was a magical experience, filled with healthy, towering corals as far as the eye could see. The image of massive brain corals stayed ingrained in my mind as I returned to the United States. Diving and marveling at the complex coral reefs of the Caribbean was, up to that point, the highlight of my life. I went on to study Marine Science and gain my divemaster rating, all back at home diving in New York. But the reefs of the Caribbean served as my inspiration, and I was eager to get back.

By the fall of 2023, I returned to the Caribbean, this time to Utila, Honduras. I lived there for five months, completed my dive instructor course, and interned as a research assistant at a local NGO. However, upon my first dives back, I was horrified by the condition of the once-pristine reefs. I had heard and read countless stories about Utila, a diving hotspot known for its pristine reefs and diversity. But the once towering pillar corals were now just skeletons, and white lesions were consuming the majority of the brain corals.

Current Ecological Crisis

Today, when you descend into the waters of the Caribbean, you’re diving into the middle of an ecological crisis: the rapid acceleration of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). This is not just another disease; it is, quite possibly, the most lethal coral plague ever recorded. It is rapid and catastrophic, capable of wiping out entire coral colonies in a matter of weeks.

During my time in Honduras, we were on the front lines, treating affected corals with antibiotic paste, a technique that has proven highly effective at limiting the spread of lesions. We monitored corals and worked to educate fellow divers on the disease and how it spreads. Crucially, we taught divers how to properly decontaminate their gear by soaking equipment, especially neoprene (wetsuits, booties) and BCD bladders, in a 1% bleach solution.

As divers, we are uniquely positioned. We are in the water, intimately connected to the reef’s condition, and we are often the first to witness the devastation. We are the first responders, the reporters, and, unintentionally, the potential vectors. It’s time to talk honestly about this unprecedented threat, how we are involved, and what an integrated, science-backed solution really looks like.

For decades, Caribbean reefs have been battered by a relentless combination of stressors, from widespread bleaching due to rising sea surface temperatures to local pollution and overfishing. But SCTLD is an entirely new level of devastation. Unlike previous diseases that targeted one or two species, SCTLD is an indiscriminate killer, affecting 21–29 different species of stony corals. This includes the Caribbean’s biggest and most important reef builders, such as the boulder brain corals (Colpophyllia natans). The disease is pushing critical species like the rare Pillar Coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus) toward functional extinction, limiting the genetic diversity needed for future recovery. While mortality rates vary, the disease hits some afflicted species incredibly hard, with reported losses ranging up to 94%.

The Devastation Reaches Curaçao

At the end of my time in Honduras, I traveled back to Curaçao for six months as a scuba instructor in the spring of 2024. When I made the initial decision to move, SCTLD had not been widely reported there, with the first cases reported only about eight months prior. I expected to return to the same pristine reefs I had left years before, the ones that made me fall in love with the Caribbean.

Instead, I found that the disease had absolutely devastated the once-thriving coral gardens. Entire brain corals, once taller than me, were completely dead and covered in algae. All in less than a year of the first reported cases. The reef health had declined so drastically and quickly, yet there was hardly any mention of it. Shockingly, the dive shop I worked at instructed me not to mention it or address it with customers. They believed it was bad for business and that disinfectants were too expensive to buy and use constantly. Given Curaçao’s position as one of the southernmost islands in the Caribbean, located just off the coast of Venezuela, the rapid spread of the disease through the Dutch Caribbean is deeply concerning and shows that the disease has successfully ravaged through the entire Caribbean.

A large Orbicella faveolata, afflicted with SCTLD. All phases of disease are shown: healthy coral tissue in dark yellow, diseased tissue in white, and dead tissue in dark brown, and consumed by algae.

Brain coral with active lesions next to already dead corals.

A Timeline of Catastrophe

The disease was first reported in Florida in 2014. By 2018, it had spread to the Mexican Caribbean, covering approximately 450 km of the reef system in just a few months. It continued to spread rapidly through the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, evidenced by a 14% prevalence in affected sites in Belize and Honduras between 2020 and 2021.

SCTLD manifests as a lesion or band of bright white tissue that rapidly consumes the living coral tissue. This progression can kill even a massive colony in a matter of weeks. As the massive, complex coral skeletons die, the reef literally begins to crumble, leading to a dramatic reduction in both live coral cover and structural integrity.

On islands like Utila and Curaçao, diving and tourism form the vast majority of their economic foundation. The spread of SCTLD is often seen along high-traffic dive routes and expands rapidly near popular tourist activities, suggesting that accelerated transmission through dive gear is highly likely. Reef collapse means diminished structure, fewer fish, and less beauty, directly causing an economic loss in dive tourism and fisheries. With the massive declines in health across the region, tourists are increasingly opting to go to further destinations in the Pacific, where reefs are still pristine.

Going forward

Divers and scientists must work together to monitor and treat the spread with existing knowledge. While the dream of treating every infected coral with antibiotics is ideal, it just isn’t realistic at the scale of the crisis. But also, more research must be done on root causes and remediation techniques. We are the eyes and ears below the surface, and our involvement in citizen science is critical. Various local Caribbean NGOs rely on precise diver reporting to accurately track the disease’s progression. Treating dive gear needs to become a required practice across the region after every single dive. This is the biggest way to ensure our dive gear is not a vector for unintentional spread. Every dive professional, every local guide, and every visiting tourist must commit to decontaminating their gear after every dive in affected waters.

Meanwhile, the scientific community must accelerate research into root causes, genetic resistance, and long-term remediation techniques, such as identifying and propagating SCTLD-resistant corals. However, without your commitment today to prioritize halting the rapid spread, the reefs they are trying to save may not survive long enough to benefit from that research. The future of Caribbean reefs and diving depends on our ability to act now.

Sources

Noonan, K. R., & Childress, M. J. (2020).

Evans, J. S., Paul, V. J., Ushijima, B., Pitts, K. A., & Kellogg, C. A. (2023).

Gari, S. R., Newton, A., & Icely, J. D. (2015).

Lee Hing, C., Guifarro, Z., Dueñas, D., Ochoa, G., Nunez, A., Forman, K., Craig, N., & McField, M. (2022).

Swaminathan, S. D., Lafferty, K. D., Knight, N. S., & Altieri, A. H. (2024).

Toth, L. T., Courtney, T. A., Colella, M. A., & Ruzicka, R. R. (2023).

Alvarez-Filip, L., González-Barrios, F. J., Pérez-Cervantes, E., Molina-Hernández, A., & Estrada-Saldívar, N. (2022).

Strategy for Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease Prevention and Response at Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. (n.d.).

Studivan, M. S., Baptist, M., Molina, V., Riley, S., First, M., Soderberg, N., Rubin, E., Rossin, A., Holstein, D. M., & Enochs, I. C. (2022).

Leave a comment